Understanding The Basics of A Paraglider’s Language.

In paragliding we step forward into the unknown every time we launch. We can only make sense of that unknown by being in the moment and responding to the wing’s communication about the parcel of air it is in as close to “now” as possible and, in a way that uses the wing’s language. Our first steps, like learning any language, are to understand by listening, and then we have a basis from which to begin speaking. We have a team relationship with our wings, and, just like in any relationship, it will serve us well to learn our partner’s language rather than expecting our wing to learn our language (which is highly unlikely in this case).

A language begins by differentiating. We have to begin by noticing movement or change. When sitting in the harness of a paraglider we notice that there are 2 hook-in points. This essentially divides our wings into 2 halves which allows us to perceive their communication differences separately. This communication is through an increase or decrease in pressure or speed on one or both sides but usually an asymmetric combination of the 2 sides, thus its nature is mostly asymmetric. Another thing to notice is that our paraglider has a two-word language, Yes/no or faster/slower. A third thing to notice is that it communicates to us primarily through our connection to it. Changes to the wing are communicated to our butt, to our hands and arms and somewhat our skin and ears by the feel and sound of the increasing or decreasing speed as it moves by our skin, helmet, lines, etc. It is fortunate that we have 2 hook-in points and thus that our wings have an asymmetric nature because it allows for more defined and varied communication from our wing. This 360-degree differential feedback is primarily communicated to our butt by the way our body is moved in the harness and through the air in relation to the wing’s changes. So, pardon me while I focus on your ass.

Step 1 is awareness. This can also be thought of as listening. Without this, all is lost; the pilot is dead to the communication from the wing. This writing can help you with the transition from being an insensitive ass into becoming a sensitive ass. Your family can thank me later.

Step 2 is Carpe Diem (seize the day). Or in our case carpe temporis (seize the moment). In our sports we mitigate risk by seizing the moment. If we are flying along noticing but not knowing how to respond to the communication from our wing, or maybe we know but hesitate, we are out of sync with the space/time moment that our wing has just communicated about. In this case your ass is noticing but the rest of you is slow to respond. This is not a very efficient way to fly as the following examples show.

Step 3 is to know how to speak “Winglistics”. We fly with “some brakes” in order to say yes/no or more/less to the wing’s communications.

Example 1:

If you are thermal hunting for the first time and you happen to blunder straight through the center of a useful thermal, the typical experience of the insensitive ass is: “WHAT WAS THAT?!” How do I know? Because I used to be one (Some of my friends think I should drop the “used to be”). For a sensitive ass this feels very different. You feel a pull in a specific direction or small drop. In 1 or 2 seconds there will be an increase in bumpiness and almost immediately the sensation of lift and a tip back in your harness as part or all of your wing enters the thermal. Through the next second there will be a solidifying of that increase in lift as you and your wing complete the transition into the rising air. 1 to 4 seconds later, another and most likely stronger and sharper increase in lift will move through all or parts of your wing as you enter the core. If you are lucky this lift will last 3 seconds or longer and then will turn into decreased lift as you move through the core and back into the periphery of the thermal (this may feel like sink to your newly sensitive parts, but your vario will confirm that it is decreased lift). One or more seconds later with bumpiness and the change from lift to sink, your wing has told you, “Elvis, you have left the thermal”. Your sensitive ass now says, “That was a thermal slowpoke, I told you it was there 8 seconds ago, what are you waiting for?” and you promptly turn back into it. Of course, this is still very inefficient. Your increased sensitivity has allowed you to recognize the communication from your wing but you are still too slow to respond to that communication. Your space/time relationship to the thermal is still “out of whack”.

The following is the experience of the perfect thermalling pilot (fictitious) that we all aspire to be in every thermal. This next example is where you really become the perfect ass.

Example 2:

Let’s pretend that you are THE most sensitive ass in paragliding. You, as the newly crowned super sensitive pilot are called Sensi, and you are currently searching for the next thermal after having left the last thermal at 2 miles above the terrain. On glide you feel absolutely NO variability in the airflow for 14 minutes. Then, there is a VERY subtle movement of some kind, somewhere in the wing. Let’s say a slight decrease in pressure within the third cell from the center of the wing. At this time, since you are thermal hunting, it is not important what the movement is, what is important is where it is. If the location is not perceivable, you will maintain the heading. If it is perceivable then you make a heading change towards the perceived location. This is an educated guess that becomes more educated by the use of it (whatever we practice we get better at). The wing communicates to the pilot constantly about the nuances of the parcel of air it is in NOW, that is just its nature. Our wing does not dwell in the past or future like we do. That is also one of the pleasurable aspects of paragliding, to fly well demands that we be in the moment. This feedback is the language of our wing. This language communicates to us through an increase or decrease in the wing’s pressure or speed that initiates in the part of the wing that first intersects with the change. This might be the right wing-tip or the middle cell of the left side of the wing or anywhere else along the leading edge (It could also be anywhere along the trailing edge telling you what you have just left). You will notice which cell in the wing is affected first by the change and the direction in which that change rolls through the wing from the leading to trailing edge, not by looking but by feeling and noticing at what angle your body is tipped back or to the side or forward. Sensi then instantly extends that line of the body movement out in front of the wing for 20 to 100 feet. This line will bisect the core or center of the thermal. If the map is anywhere near accurate, you will intersect with the lift in some fashion. This sensitivity has now purchased a thermal that otherwise would have been missed. Now Sensi’s wing is intersecting with the initial sinking just on the outside of the bumpy edge which almost instantly becomes the initial lifting of a particular one to 3 cells along the contacting edge of the wing. Unlike our newly sensitive ass from example 1 above, Sensi not only perceives the information from the wing but also knows how to immediately communicate back to the wing in order to place it in the most advantageous position. This new information by the part of the wing that is “talking” allows Sensi to mentally draw a line through the wing as it is sensed by the body’s movement, which is a result of the wing’s communication to Sensi. Our perfectly sensitive pilot can now extend that line to intersect the core’s center and steer to follow that line with the intention of meeting the core with the wing tip that is more efficient. This usually means 10 to 30 degrees off either direction from that line (whichever takes the least degrees of rotation) intersecting the edge of the core with the right or left wing-tip. Ideally the turn direction remains constant and coordinated, smooth and ballet like. This is efficient. Taking 987 degrees of rotation to center in the core (which is the norm for an insensitive ass) wastes a lot of time and altitude.

Sensi makes a perfect guesstimate, feels the right wingtip rise, immediately turns right and is centered in the core in less than 10 degrees of rotation, since the initial feel of “something” while thermal hunting. Sensi, of course, is only perfect because we imagine it is so. This kind of perfection in mapping a thermal (or any other part of life) is difficult to achieve, there are too many variables that are not known by us, not the least of which is that we can only sample one minute part of a very large, varied and ever-changing part of nature. We are mapping the thermal by taking a dynamic four-dimensional part of nature and making decisions about its nature (size, shape, position, speed, movement pattern, etc.) one to 6 seconds from now, taking a mental snapshot of it, freezing it, making it into a static object, analyzing it as such and extrapolating about its future. While we are doing this it is not stopping and waiting for us. Which I am thinking is a good thing. (I cannot imagine the trouble we could get into if we could stop the dynamic nature of life.) Nonetheless, we can get better at Winglistics through paying attention, knowing what to pay attention to and disciplined practice.

Once we are centered in the core or thermal the work is not over: we usually need to recenter often, which is accomplished by elongating our circle for 1 or 2 seconds. This does not mean flattening the glider out but doing a small side slip that moves the glider into the greater lift 2 to 4 ft. (More about this in part 3).

Sensi knows that thermals are, generally speaking, roundish. With this assumption it can be deduced that if the right wing-tip is the only part of the glider that is initially lifted up or bumped by the edge of the thermal, then the core or center is 90 degrees off to the right at that instant. If the pilot is heading in a compass direction of 360 degrees, then the center of the core should be on a compass heading of 90. Keep in mind that, this is an idealized thermal that is round with smooth edges and is in no wind AND that no thermal is like that. However, this is usually a good enough estimation to put the pilot “in the ballpark”. Fortunately, while we are working on finding the core of the thermal, the wing continues talking to us which then allows us to adjust our mental map as necessary to create increased levels of efficiency (maximum lift or reduction in sink).

Our perfect pilot understands the language of the wing and where, when and how to place the wing for maximum efficiency. A paraglider’s language is a space/time language that demands that the pilot (the only one in this relationship with any brains at all) responds immediately. Our wings truly have the most severe form of ADD ever diagnosed. It literally never stops talking, even while we are talking to it, it just keeps jabbering away. If we have to think about what happened and how to respond for the greatest efficiency… It’s too late. Our wing has already moved on to 9 new messages for us. This requires three things: being in the now (as much as possible), an intimate body knowing of the wings language and how to speak Winglistics without hesitation.

How the wing communicates the details of the parcel of air it is moving through is primarily by how it moves our body in the harness. Visualize the way your body is being moved when your right wing-tip is lifted up. As Sensi (I know that is a stretch, just go with it) when your right wing-tip rises you feel an increase in the pressure or weight on your right butt cheek. A fraction of a second later, your right hip rises and your torso flexes at the hip. Then your right shoulder rises and your head tips to the right flexing at the neck. Since you are Sensi you are in the moment and you realize that this communication from the parcel of air that is hugging you and your glider is saying “Hey! The lift you are looking for is 90 degrees to your right.” As Sensi’s hip begins to rise the hand and hip increase the pressure further by digging in on that side to immediately begin the rotation toward the indicated lift. This communication from your wing is clear, precise, and perfectly honest. If your perception and response are also, then you have achieved the experience of perfection in the moment (which is the only place it can be found). These are fleeting, magical moments that occur in fits and starts at first. They come and go in a flash and yet within that moment, a pilot can experience eternity, IF you are HERE NOW. It helps if we prepare ourselves by first learning our wing’s language cognitively and viscerally. This gives us the opportunity to just do, without much or any thinking. It becomes like walking. We just do it.

However, if you are still an insensitive ass then you will not be in the moment and will be late in your perception of, and response to, the information. This delay usually ends up with misinformation being the perceived information and therefore confusion. Our delay distorts the time/space and turns it into deceitful information thereby misleading us. We therefore turn left going away from the lift or we go straight and repeat our old mantra “what was that?” Why do we do that? Because most of us do not like confusion and go away from whatever we think is confusing us, usually subconsciously. It takes a disciplined mind to move into confusion in order to reach clarity. This is a love of learning. The endorphins associated with deep learning are primal, and pleasurable if approached with an open mind and heart. Those endorphins are stopped by fear, and so is the learning and the joy.

To become efficient in thermalling we must perceive and respond as close to the moment of NOW as we can. What is the best way to get you started in your sensing and responding process? Do ground and simulator exercises that you can repeat dozens or hundreds of times without the added and confusing information that nature gives us when we are flying. It is best to add the flying later, after you become ass sensitive. Get the thinking and hesitation out of the way while on the ground focusing on only one isolated aspect of your wing’s language at a time. Your learning curve will be 3 to 5 times steeper and safer. Confusion seldom creates more safety in the short run but (if you survive the learning process without too much physical, mental or emotional damage) it greatly increases clarity and safety in the long run. Monitoring and managing change and energy within the wing’s active space/time opportunity, is the way we use the wing’s language.

This was the synopsis of Winglistics. It is a model that works for me and I hope it will be helpful for you.

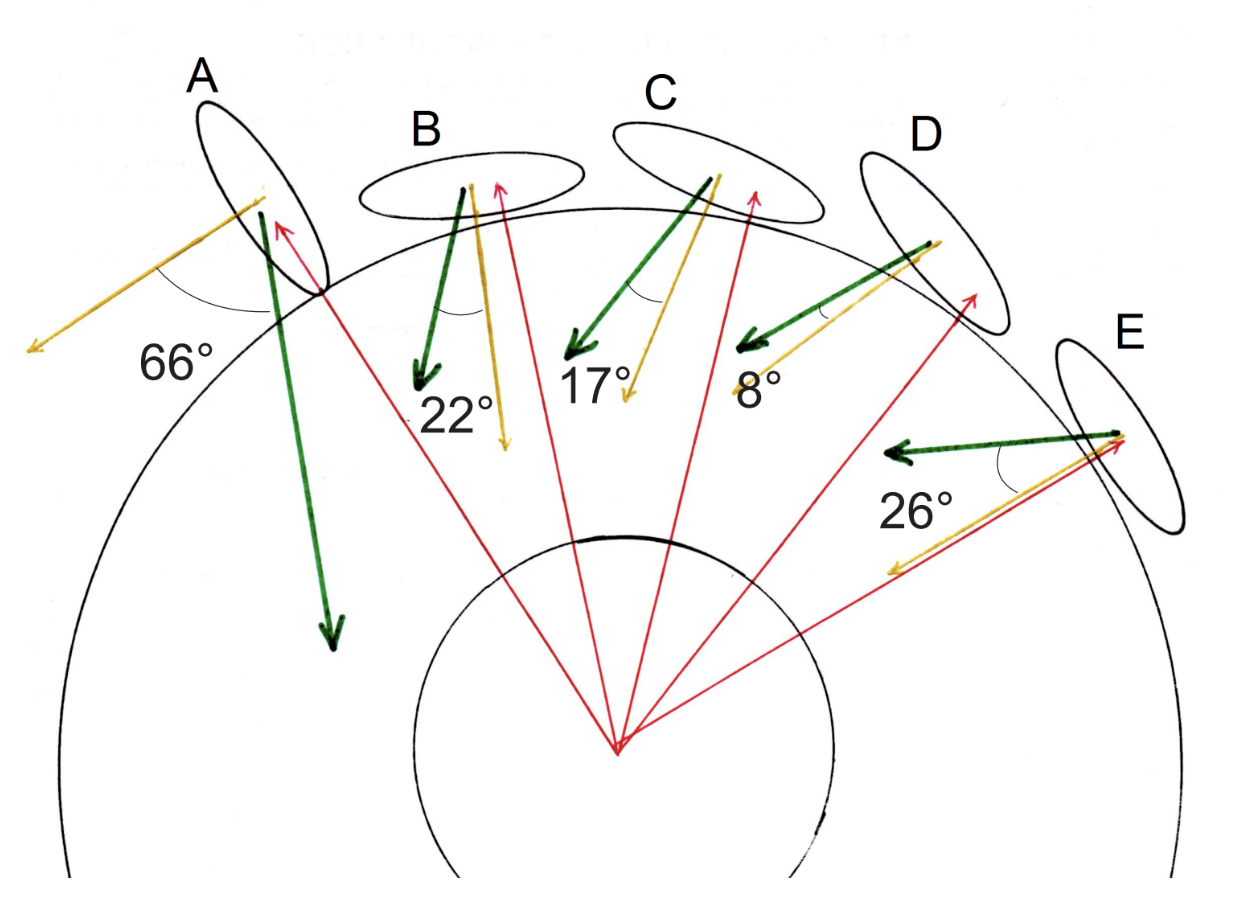

This drawing shows an idealized thermal and core with gliders A thru E intersecting at a variety of angles. The gold line/arrow shows the direction of travel for each glider at the moment of thermal contact. The red line/arrow shows the direction the pilot’s body is tipped back and to the side during contact. The green line/arrow shows the direction the pilot should immediately go in order to intersect the core with the left wing tip, resulting in being centered in the core in less than 90 degrees of rotation. Pilot A’s body is tipped at an angle of 90 degrees to the right from the direction of travel. That communication from the wing is saying the thermal edge and most likely the core are, at that moment, 90 degrees to the left. The most efficient way for the wing to intersect with the core is with the left wing tip which allows for an immediate left turn creating an immediately centered circle, with the proper amount of elongation, i.e. a 20 second circling turn.

Gliders B, C, D and E all show differing degrees of intersection and adjusted angles of approach to the core. This is an approximation because every thermal is different and none are perfectly round. Nonetheless this drawing gives us a visual that we can use as a mental model to create more accuracy in our use of the fluid nature of a thermal. Being able to center the core (if there is one) within 5 to 90 degrees of rotation can create thousands of feet of useful altitude.