Is this really possible?

Reading an article in the journal “Science News” and seeing the movie “Wired to Win” got me wondering just that.

The article was about Chess Grandmasters and how they achieved mastery. The research concluded the following:

- Chess Grand Masters do not plan ahead with their moves. They simply look at the board and the next move appears or jumps out at them within 3 seconds.

- That any normal human being can achieve grandmaster skills through time and dedicated practice.

- It takes about 10 years of focused effort to reach the grandmaster level for just about anything we humans under-take.

- With enough practice and repetition, the chess grandmaster can process all the information and input of a game as complex as chess, and produce the best response in less than 3 seconds. This is impressive!

The movie (focused on the Tour de France, an annual men’s multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. It consists of 21 stages, each a day long, over the course of 23 days.), showed how the brain cell firings work in sequence and relatively slowly at first until the skill we are attempting to learn works well and we repeat it a number of times. Then the firings happen in quicker succession until, through practice, they happen all at once, without trying to figure it out (thinking without effort). This is the beginning of mastery of any skill be it child care, chess, thermalling, dishonesty, archery, etc.

Conclusion; whatever we choose to practice, we get better at and with a lot of persistent practice we can master a complicated skill in about 10 years.

When new pilots are learning how to master thermalling skills, at first it is difficult and time consuming because their timing is off, their ability to process all the information is slow and cumbersome, and their practice-time in the air is short and infrequent. Through repetition, however, their brain begins to process the sequence more and more quickly until the brain firings happen all at once and they begin to react quickly enough to keep up with the wing and the parcel of air they are in. The brain cell firings become instantaneous and automatic. We usually refer to this as muscle memory, but I believe, and these resources seem to confirm, that we are simply creating a mental “rut” that makes it easier and easier to process the input and therefore takes less time to execute an efficient response; so much so that it seems to take “no time”. In paragliding, if you have to think about it, usually it’s too late. Once we get our hips to respond automatically to certain communications from the glider it frees our mind up to work on another skill set. For example, moving our hands appropriately or noticing the recent changes in the sky. When we master one skill, it frees our brain up so that we can work on mastering another. When 10 or 15 skilled responses become automatic, a pilot begins to master thermalling.

Thermalling is particularly tricky to master for 3 reasons:

- We cannot see the thermal, and most people (with few exceptions) are heavily visually oriented.

- Weather. We can’t practice thermalling every day because the weather and life get in the way. Remember, mastering something takes consistent, frequent repetition with disciplined effort. (This is why the ground bound exercises for practicing the separated component parts of thermalling are so helpful)

- It is a 3-dimensional experience. (Forward/back, side/side, up/down,). Most human beings are accustomed to thinking of and relating to forward/back and side/to side but not so much with the up/down dimension. Birds and fish are much more 3-dimensional than the dirt bound species, it is relatively new for us to process and to use the up/down to our advantage. We are not hard wired for it.

My personal deepest 3-dimensional experiences that have helped me with this learning have been:

- Figuring out the 3-dimensional connections of a construction project. (thus my admiration for carpenters)

- Scuba Diving

- Thermalling (particularly with eyes closed, not safe to do in flight traffic or near terrain, it is a process of learning to let go of the planet surface)

- A deep state of meditation. (More than 4-dimensional)

Sixteen of the most important skills to develop in order to master thermalling are:

- Expanding into 3-dimensional thinking.

- Sensing (noticing the details…we can’t respond appropriately if we don’t notice).

- Responding efficiently, effectively and immediately (active piloting). Thinking of this as something that we do for our safety is fear producing. Thinking that we do it for efficiency is more realistic and relaxing. I don’t know how many surges I have had in paragliding, probably hundreds of thousands or millions (my calculated guess is 3-3.5 million surges: 15,000 flights, over 2,000 hours of airtime. Of these only 2 have been unfriendly. I like to think of the surges as our glider jump-starting itself again. Stop thinking about controlling the energy in the glider and start thinking about managing it. Don’t fight it, instead use it to produce the desired result. The parcel of air we are in is constantly feeding varied amounts of energy to different parts of our wing. When thermalling, we are constantly using that energy reserve to our advantage in order to efficiently produce altitude and glide, on scales that range from minute to large.

- Altitude management (energy conservation; balancing patience with pushing, when to use speed or wait, or top out the lift or leave early).

- Mapping (noticing the nuances of shape, size, strength and fractal pattern of the thermal).

- Elongating (into the increasing lift or downwind).

- Shaping turns (to be most efficient with your map, i.e. # 6).

- Remembering (your 3 last turns influence your next turn, thermals and clouds are fractals, we will talk about fractals later).

- Anticipating (this, and # 8, add a 4th dimension: time).

- Coring (don’t waste time in the thermal, work the core, if there is one.)

- Reading the sky (knowing how, what has been, and what is, creates what will be, and where in the sky it will be).

- Reading the ground, thermal triggers, and generators and ground tracking to maximize time and distance (thanks Peter Grey and Dennis Pagan for the great debate on this in the magazine a few years ago).

- Conservation of flying days, (very few pilots can afford to spend 8 hrs. every day on flying) predicting the weather is another never ending mastering process & economizes your time.

- Flexing with what nature delivers (change your flight plan or thermalling strategy when necessary and stick with it when appropriate).

- Repetition (patience and persistence, with thermalling you will either teach yourself patience or impatience. You get to choose which.).

- Be at peace with your abilities. Once you have mastered the above, be at peace with your abilities no matter how they compare with someone else’s. Brain cell firings happen more reliably, freely and instantaneously when we are relaxed and at peace.

When separated into these component parts some of these can be practiced on the ground in your yard, living room, or simulator. If you haven’t figured out thermalling yet, you can get 3 years worth of mapping practice done in 15 minutes in your living room. Remember, when you master one skill it frees your mind up to work on another, it is impossible for a human brain to work on all of them at once. None of us will ever get perfect at all of this, but we can get better, and the difference between 50% and 51% accuracy can be measured in miles.

My 2006 was so highly successful for XC that I was perplexed to come up with a reason as to why this was, until I researched this article. The year was not any better for XC weather, in fact other pilots in Utah had complained about what a terrible year it was. I didn’t have any more time to spend on it, and I had been flying the same kind of performing glider I had for the 2 previous years. I was doing a better job of prioritizing and selecting the better XC days and therefore wasn’t having as many short XC flights (under 20 mi). I actually had fewer days than normal where I was attempting to fly cross country in ‘06 and yet had seven times greater success. Why?

I have come up with 3 possible reasons and almost certainly my success was a combination of all 3.

- Luck: (Bill Belcourt says “Luck is always a factor. The magic is in how you use it when you get it”)

- Repetition: I had been practicing since my first thermalling experience in 1989.

- Meditation, which I have been practicing and teaching since 1969.

This particular year I had been chanting and meditating more than usual during my XC flights. I have found that meditation has accomplished 3 things that have helped my thermalling and decision making.

- I am more relaxed (CBS news had a piece on 1-18-07 on how stress reduces the size of and # of connections of neurons in the brain).

- I think less (less clutter equals more ability to be fully present).

- I am more lucid (Lynn Cyrier once shared with me, “Fly from the inside out, not from the outside in”.)

Flying in a more relaxed state, means I overreact less. Thinking less, means I do less over-analyzing or second guessing of myself, and both of those give me more clarity so that I “do” rather than think, debate and then “do”. I am therefore able to minimize the actions I perform in the thermal and stay current with glider input and response time. My ground track, cloud tracking and sky reading was also more automatic and accurate. The result has been that I was more consistently in the right place in the thermal and in the sky.

Marcel Vogel and other brain researchers have said that at any given moment there are about 10,000 brain cell firings going on related to stimuli from our senses, and of those 10,000 only 9 can come to consciousness (if you are a genius). Our job in mastering thermalling is to find a way to bring the most productive 9 (for a successful outcome) to consciousness and to have the rest become so automatic and non-conscious that we can reserve those precious 9 bits for the most important, satisfying and immediate parts of our thermalling moment. And yes, of course it must be pleasurable or satisfying or we would not endeavor to repeat it.

We have all seen friends get out of the sport because it ceases to be satisfying for them. They either get too scared or frustrated or choose some other emotional state that they find less than satisfying. Often this happens because they attempt parts of the sport that they are not yet ready for, or they don’t stretch themselves enough to stay interested and instead focus on their fears or limitations.

There are many skills that must be developed and then cohesively merged together to create a consistently successful outcome. For a chess grandmaster, the skills are about looking at, and studying many different boards and potential moves for many years. For thermalling, it is, at a minimum, the 16 previously listed skill sets practiced on the ground, in your head, in the air, and, (through repetition), applying them lucidly when necessary and non-consciously as much as possible.

For those of you who already know thermalling, this may seem overly complicated because all or most of this is already automatic for you. I hope you still find it useful for clarifying what you are doing.

For those of you starting to learn, working on one skill set at a time will increase the speed and safety of your thermalling process. The highly simplified version of this class is, in the words of Todd Bibler, “When you’re going up, turn.”

When flying there are only 2 things we need to do to create safety: manage the proximity to hitting any hard surface or object, and keep your glider away from stall.

The “Science News” magazine article on chess grandmasters, the movie “Wired to Win”, and a good XC year have all motivated me to explore, through this article, how to achieve better thermalling skills and experiences. I have realized for many years that working on slowing down and separating the step-by-step process of what actually contributes to more successful thermalling flights greatly assists one to progress more quickly. I now understand why. Writing this has been useful for me, thanks for the opportunity.

MASTERING THERMALS part 2

by Ken Hudonjorgensen

Fractal patterns in thermalling

References “Fractals Everywhere” by Benoit Mandelbrot and www.fractalfoundation.org

“A fractal is a never-ending pattern. Fractals are infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales. They are created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop.” Reference taken from www.fractalfoundation.org

Fractal patterns are a kind of “dance” in nature that moves in and out, through big and small, and through anarchy and order, that start out as seeming to be anarchy and as they are studied, reveal more and more order. If we can map a small thermal down low it will tend to repeat itself as it grows.

We use our memory to follow the pattern of the thermal and the day to create efficiency. Each time-period has a fractal pattern to the thermal, sky and spacing of thermals and clouds. This pattern is why we get increased lift at a certain compass heading every time we complete a circle in a particular thermal and position and bank angle. So, unless we change our track within the thermal by elongating or tightening our radius, we will continue to be inefficient by working only one section of the strongest part of the thermal. When we make adjustments as we rotate in a thermal, we are following the fractal pattern of the strength of the thermal. If we can stick with that strength as it moves, grows, merges and changes we will effectively maximize our rise in the parcel of air we are in.

There is also a vertical fractal pattern to the strengthening, organizing and weakening of thermals for a particular day and time period whether it is a particular hour in the day or time of the year. Do they tend to weaken at 16,000 ft. or organize at 4,000 ft. or have the most mixing at 10,000 ft.? Many things, (known and unknown), can affect our thermal.

Some of the known effects are

- Thermals joining together

- A particular terrain,

- Cloud feature concentrating lift

- A reservoir of potential

- Wind shear

- Top of the lift, etc. etc…

If we learn to flow with the fractal patterns and predict their progression into the present and future based on their past, we become more efficient. Chess grandmasters can see the fractal patterns of each board they look at in less than 3 seconds. That is why they can play 20 masters at once and beat all 20 of them.

For thermalling, this is a combination of being in the present moment, remembering the recent past – 5, 10, 15 seconds ago; the not so recent past – one minute, one hour, when the day started, last year at this time; and anticipating the future –

- where the strength of the lift is going to be the next time I come around in this circle 2 or 3 turns from now

- where I want to be in the sky or over the terrain in 10 min. 1 hr. or 5 hrs. from now

- how long the thermals will stay strong

- when sunset will be today

- based on the prediction for the day

- what yesterday or last year were like, and

- when the lift will likely be usable today.

We attempt to align ourselves with the fractal pattern of the thermal or the sky, the time of year, the site we are at, etc… Remember, from the first article I wrote entitled Mastering Thermals – Part 1, that most of these skills need to become automatic if we are to have much of a chance for success and that they become automatic through repetition over time.

There are fractal patterns to the wind through a particular weather system. For example, we have had a high-pressure system dominating in Utah for the last 5 days and every day at about noon the wind at the south side of the Point of the Mountain in Draper, UT has increased by 8 to 12 mph for 3 to 5 hours. This is a fractal pattern that is part of the fractal pattern of this particular high-pressure system.

We attempt to match our brain cell firings with perceptions and responses that produce a successful outcome in relationship to the parts of nature that we are playing with. The more often they match, the more successful we are.

Glider useful thermals

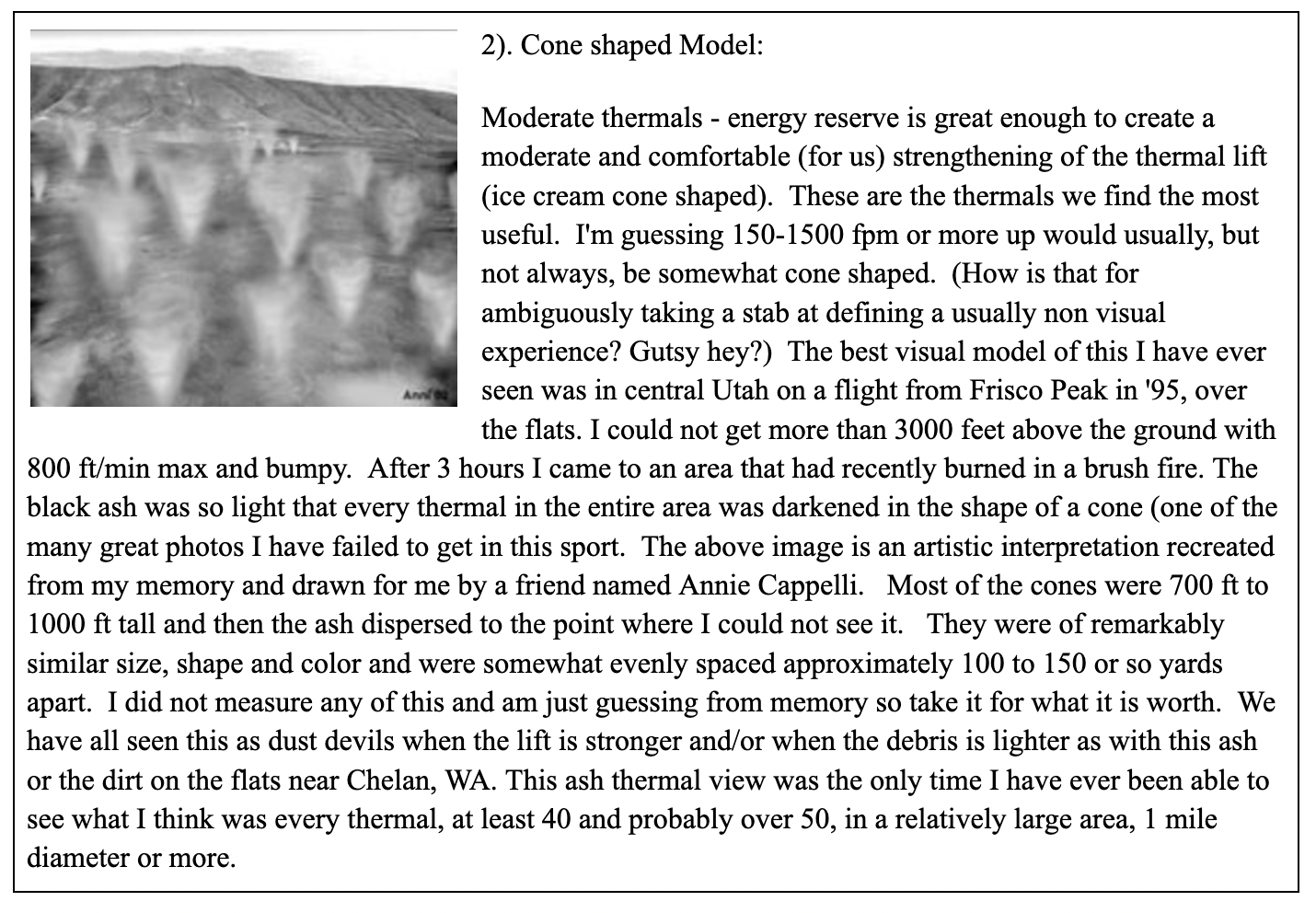

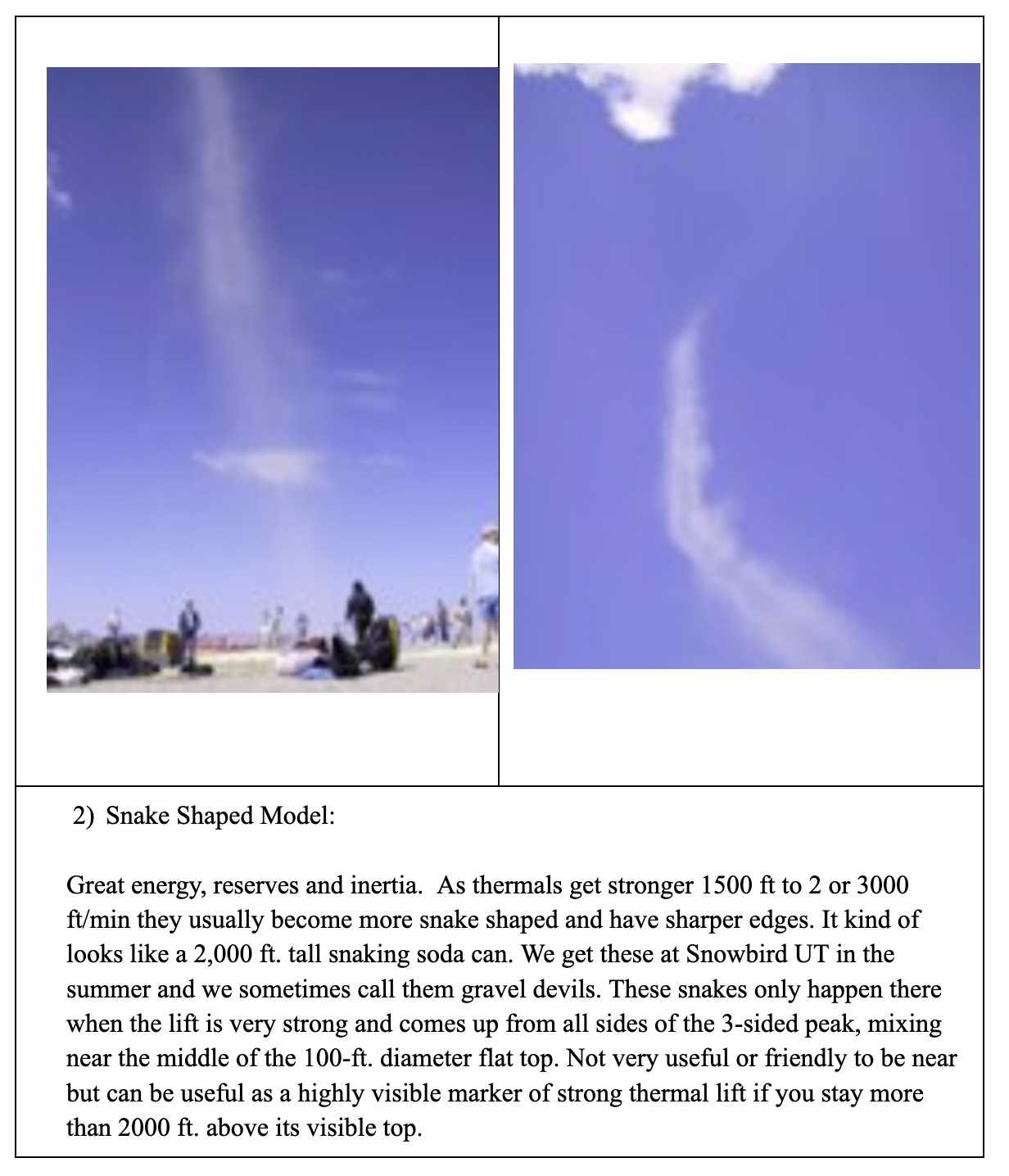

There are three generally shaped thermal categories that are useful to me as a foot-launched, non-motorized, pilot: amoeba, cone, and snake. Each of these models, of course, is variable and they meld and mix into one another such as amoeba cones and snake cones but I don’t think we get amoeba snakes – the energies are too dissimilar.

Each category creation has to do with energy reserve and inertia. How much and how quickly has the heating been happening. Is it happening now and how long and strong will it continue to happen? The energy of a thermal, of course, has to do with more than just heating, otherwise, we would only have to check the temperature differential between degrees and amount of time to figure out if it is going to be a good thermal day. But it is not just the lapse rate that we check. We also check the jet stream, the pressure and moisture content of the ground and air, top of the lift and lifted index and k-index. We look at the sky, feel the cycles etc… There are also many things we don’t understand enough about yet to even understand that we should be checking it, or how to check it or what “it” is. If this were not true, we would be 100% accurate on our thermal predictions every day. I have not yet met the pilot who can do that.

These 3 models mix and bleed into each other and are never ideal. I have seen, felt and experienced them being useful to me while flying.

This article has been an attempt to expand our understanding of thermalling. There are certainly additional and alternate ways of thinking about, teaching and doing this complicated yet simple task.